A team of researchers has summarized recent advancements in solid-state anode-free batteries, identifying existing research gaps and shedding light on factors that could enhance their performance.

Anode-free solid-state batteries: where do we stand?

They represent the cutting edge of electrochemical energy storage, promising higher energy density, streamlined production, and lower costs than today’s lithium-ion units. Solid-state anode-free batteries are an advanced technology poised to outperform conventional lithium-ion systems—but not without overcoming fundamental challenges first.

In the United States, a team of scientists from the Mechano-Chemical Understanding of Solid Ion Conductors (MUSIC) project, led by Kelsey Hatzell, associate professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at Princeton University, has compiled key findings and insights that could help solve some of these challenges.

The research behind MUSIC

“Solid-state batteries have the potential to revolutionize energy storage technology, but a major challenge is developing a scalable production process,” said Jeff Sakamoto, energy storage expert and director of MUSIC. “Hatzell’s work plays a key role in advancing solid-state manufacturing processes, and her research with MUSIC is an example of how integrated research approaches can tackle complex, multidisciplinary challenges.”

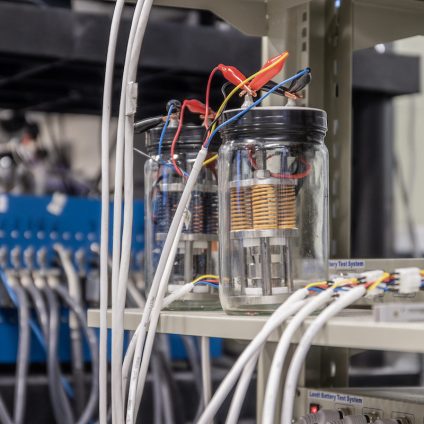

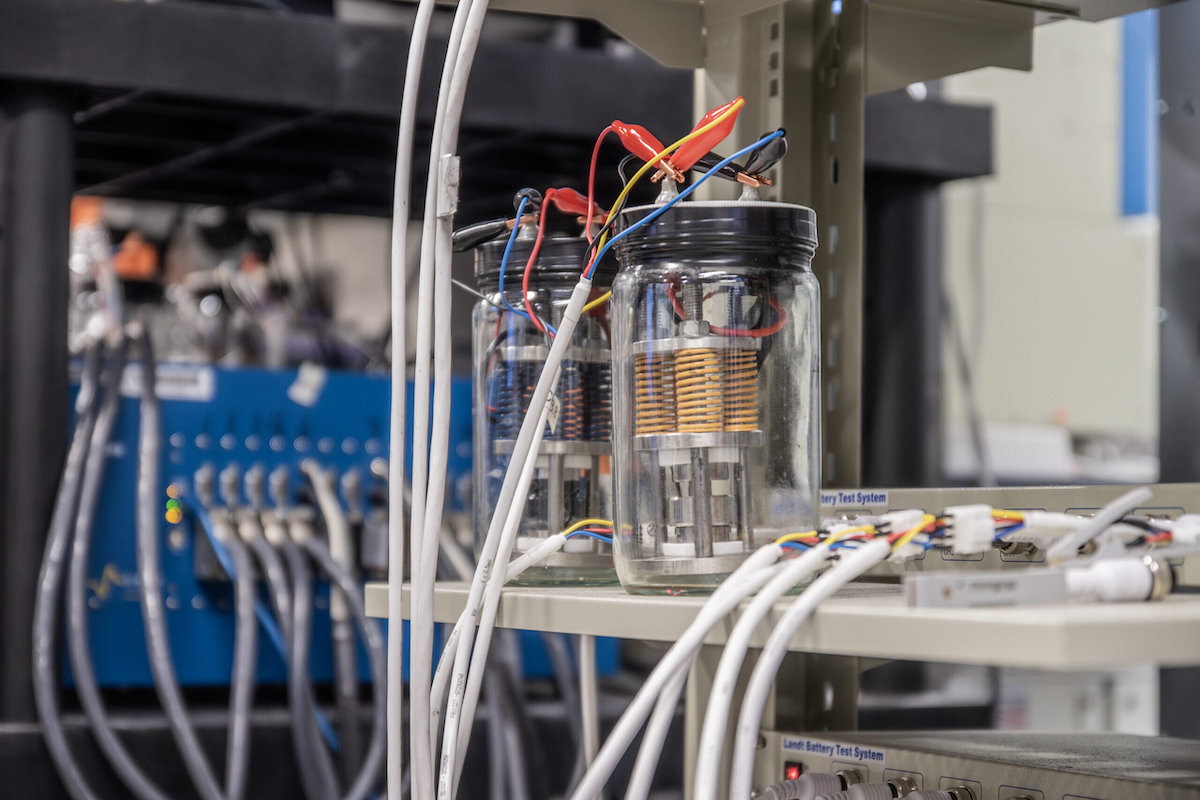

Along with a team of colleagues, Hatzell examined the state of anode-free solid-state batteries in a paper published on January 2 in Nature Materials, summarizing recent progress and identifying existing research gaps. At the same time, she contributed to two additional studies exploring the interaction between the electrolyte and the current collector in these batteries, as well as ways to ensure uniform contact.

What are anode-free solid-state batteries?

Also known as lithium reservoir-free batteries, anode-free solid-state batteries are electrochemical units that lack an active material in the negative electrode at the time of manufacturing. Instead, the active material from the cathode (positive electrode) compensates for this absence.

During charging, lithium ions leave the cathode structure (deintercalation) and migrate directly to the current collector at the opposite end of the battery, forming a thin metal plating that acts as the electrode. During discharge, this lithium metal electrode is removed.

This anode-free architecture offers multiple advantages, starting with a significant reduction in anode volume, allowing for higher energy density and more compact overall battery size.

Additionally, lithium reservoir-free solid-state batteries simplify the manufacturing process by eliminating the need to produce ultra-thin metallic lithium anodes (<25 μm) at an industrial scale.

Ensuring uniform contact between the electrolyte and the current collector

Despite these advantages, technical hurdles still stand in the way of commercializing these batteries. One key challenge is ensuring a consistent interface between the solid electrolyte and the current collector. This factor is crucial for enabling ions to move efficiently through the electrolyte, deposit uniformly onto the current collector during charging, and detach cleanly during discharge.

Hatzell and her colleagues demonstrated that a thin coating between these two components can improve ion plating and removal. Their research focused on using interlayers made of specific coatings, such as carbon and silver nanoparticles.

By analyzing their structure and composition, the researchers discovered that silver forms alloys with lithium ions, facilitating uniform plating and removal—provided the particle size is optimal.

- Larger silver particles (200 nanometers) lead to irregular, thin metal structures on the current collector, reducing battery performance and increasing failure risk.

- Smaller silver particles (50 nanometers) create denser, more uniform structures, resulting in batteries with greater stability and higher power output.

These findings offer a clear roadmap for designing interlayer coatings and optimizing the operating conditions of anode-free solid-state batteries. The study was published in Advanced Energy Materials.

The next challenges ahead

While the technology has shown success in laboratory settings, scaling this process for industrial manufacturing remains a significant challenge. However, researchers are optimistic, given the growing global interest in solid-state battery advancements.

“The real challenge will be transitioning from research to real-world applications in just a few years,” said Hatzell. “I hope that the work being done at MUSIC will drive the development and large-scale deployment of this next-generation battery technology.”