Deep sea mining in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone still harms marine ecosystems after 40 years, with biodiversity far below surrounding areas

A groundbreaking study has found that deep sea mining leaves a long-lasting mark on marine life—even after four decades. In 1979, one of the first experimental mining tests was conducted in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), a vast area of the Pacific Ocean between Mexico and Hawaii. Today, 44 years later, biodiversity in the disturbed zone remains significantly lower than in untouched nearby regions.

The research, published in Nature, comes at a crucial time. The International Seabed Authority (ISA) is currently negotiating international regulations that could open the door to commercial-scale seabed mining. Deregulating this practice, scientists warn, could dramatically increase environmental damage in one of Earth’s most fragile ecosystems.

Deep sea mining’s environmental footprint endures for decades

The study was led by British research institutions, including the National Oceanography Centre in Southampton and the Natural History Museum in London. It focuses on the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, a 6-million-square-kilometer area rich in deep sea minerals like copper, cobalt, lithium, manganese, iron, and zinc—resources deemed critical for the global energy transition.

Driven by rising demand for clean energy technologies, several companies, backed by small Pacific island nations, are seeking to mine these resources from depths of 5,000 meters. However, much of the CCZ’s ecological dynamics remain poorly understood. This new study is one of the first long-term assessments of the environmental impacts of deep sea mining.

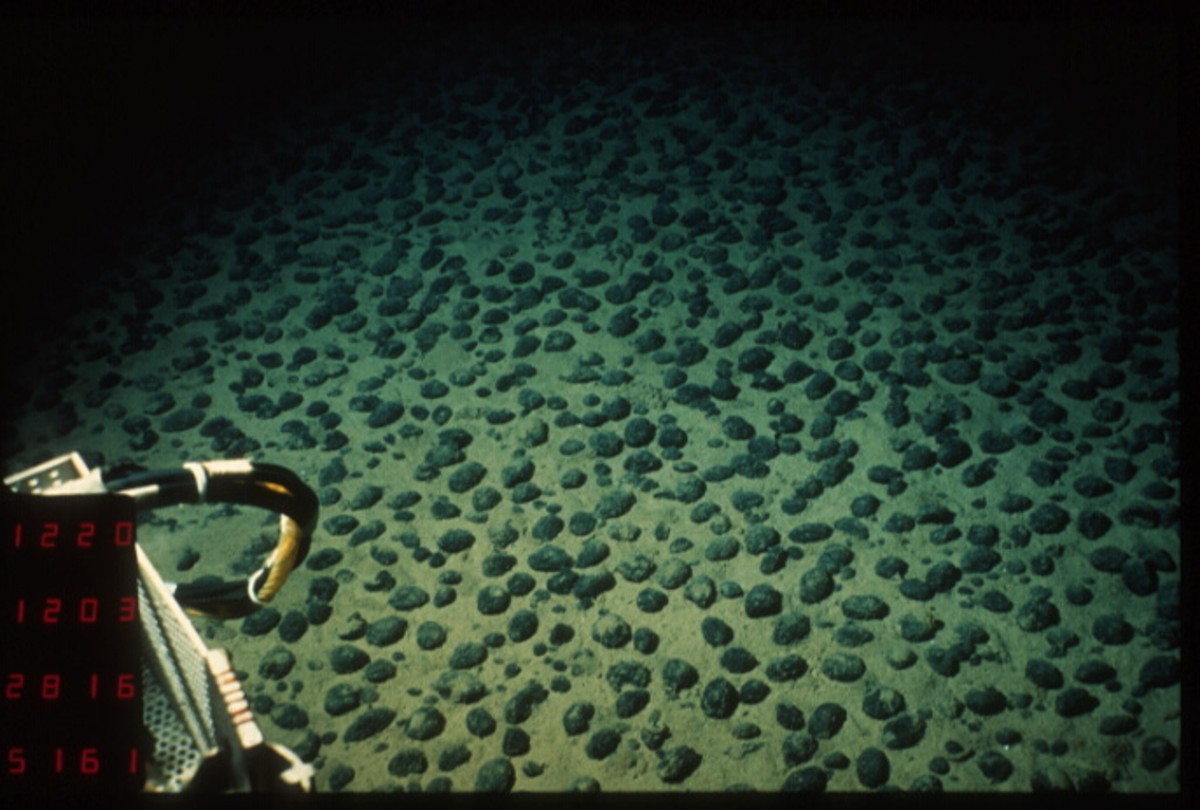

Between 2023 and 2024, researchers revisited a specific site in the CCZ where a 14-meter-wide prototype machine ran tests in 1979, using rotating rakes to harvest polymetallic nodules, potato-sized lumps of mineral-rich rock that take thousands of years to form. These nodules are not just valuable mineral deposits; they also host specialized ecosystems.

The machine left an 8-meter-wide trail of disturbed seabed, stripped of nodules and deeply scarred. Researchers found that animal populations within this trail remain far below normal levels, even after 44 years. Some signs of recovery are emerging, but the damage is still clear.

Long-term harm from sediment plumes and mechanical disruption

According to the study, the immediate extraction of nodules causes mechanical damage to the seafloor. It removes hard surfaces where benthic species live and compacts the sediments. But the impact doesn’t stop there.

The mining process creates sediment plumes, clouds of disturbed particles, that can spread far beyond the mining zone. These plumes may have significant effects on nearby ecosystems, smothering filter feeders and altering chemical conditions in the water.

The researchers conclude that deep sea mining could cause large-scale, long-lasting harm to marine habitats. As global demand for rare minerals grows, the study serves as a stark reminder that technological progress must not come at the cost of ecological collapse.