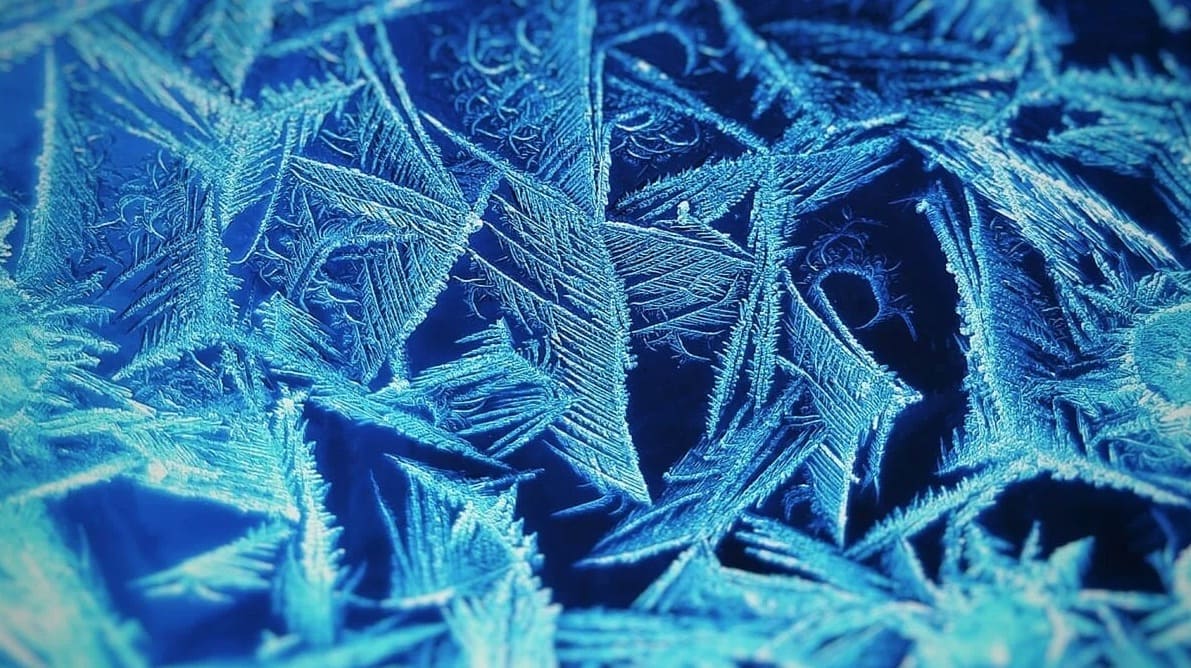

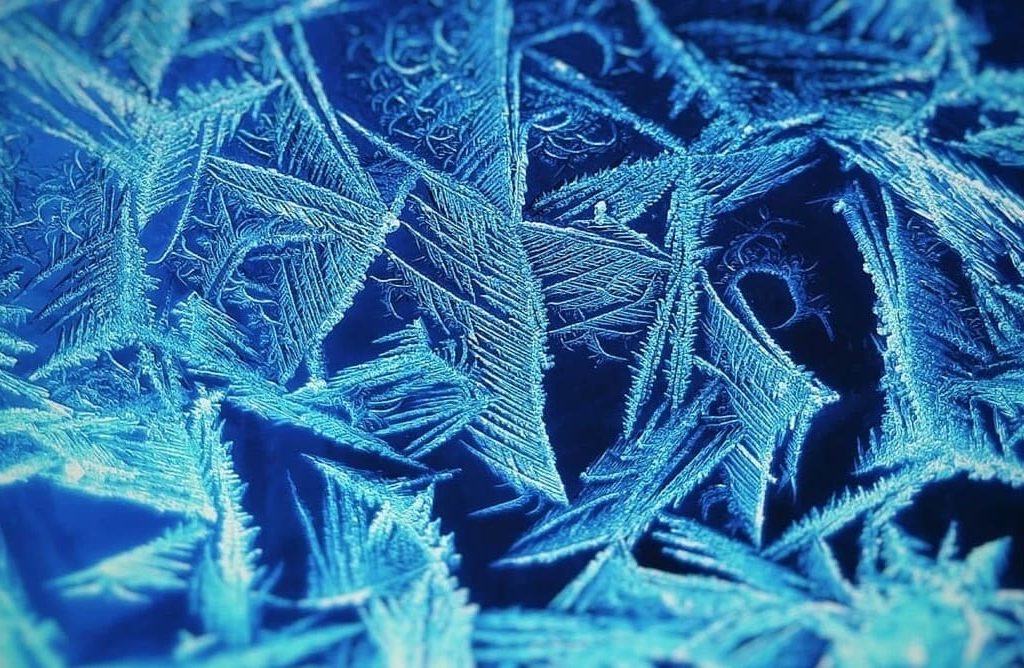

This is the warning issued by the State of the Cryosphere 2024 report, coordinated by the International Cryosphere Climate Initiative (ICCI) and released during the COP29 climate conference in Azerbaijan.

The degradation of frozen ecosystems worldwide will have “disastrous and irreversible” consequences on the state of the cryosphere, even if we implement every climate commitment we have announced and enshrined into law. Global temperatures are projected to rise well above 2°C, and the longer we delay tackling global warming, the higher the price we will have to pay. This issue should resonate particularly now, as climate finance takes center stage amid the (disappointing) outcomes of the COP29 climate conference in Azerbaijan.

The costs of losses and damages (loss & damage) will escalate, becoming extreme under the current emissions trajectory, which points toward a 3°C increase. Such a scenario would see many regions facing sea level rise or the loss of water resources “well beyond adaptation limits within this century.” Additionally, mitigation efforts become more expensive due to feedback effects triggered by permafrost thaw and the loss of sea ice.

This is the warning issued by the State of the Cryosphere 2024 report, coordinated by the International Cryosphere Climate Initiative (ICCI) and released during COP29.

State of the Cryosphere 2024: 3 Scenarios, Few Good News

The report analyzes three global warming scenarios:

- Impact of current climate policies based on national climate plans (NDCs), which foresee a temperature increase of 2.3°C and a peak CO2 concentration of about 500 parts per million (ppm).

- Business-as-usual scenario, which maintains the current emissions trajectory and leads to a rise of 3–3.5°C by 2100 and 650 ppm.

- 1.5°C-compatible scenario, where the CO2 peak reaches 430 ppm.

In the first scenario, the global temperature increase will cause irreversible damage to the entire cryosphere: glaciers, permafrost, and polar ecosystems, with consequences for sea levels. The socio-economic consequences would be devastating: increased adaptation costs, loss of infrastructure, agriculture, and livelihoods.

In the second scenario, accelerated melting of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets would result in sea level rise of up to 15 meters by 2300, irreparable damage to marine and terrestrial ecosystems, and the collapse of mountain ecosystems. This outcome is driven by positive feedbacks from permafrost thawing and the associated methane emissions. These emissions would be equivalent to the current volume of China’s emissions.

In the third scenario, the damage to the cryosphere would be minimized (though not entirely avoided). Sea level rise would slow down, and there would be partial preservation of glaciers (up to 50% in Asia and South America). The impacts on polar and coastal ecosystems would be considered manageable. However, slow-onset events would still have significant long-term impacts: even with 1.5°C, sea levels will continue to rise in the centuries following 2100, with risks of increases of 6–9 meters. But at a rate manageable for adaptation.

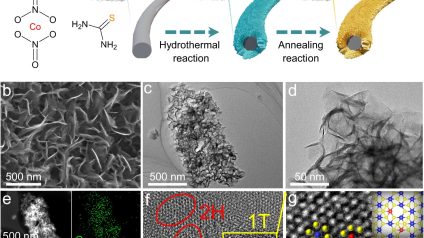

The following table summarizes the consequences for the cryosphere in each of the three scenarios, focusing on: polar ice sheets and sea level rise, glaciers and snow cover, polar oceans, permafrost, and sea ice.