With the endorsement from Liberia and Panama, the two largest ship registries in the world, the coalition of countries supporting a global shipping emissions tax now represents 66% of the global fleet and 1.6 billion gross tonnage.

What Is the Flat Tax on Shipping Emissions?

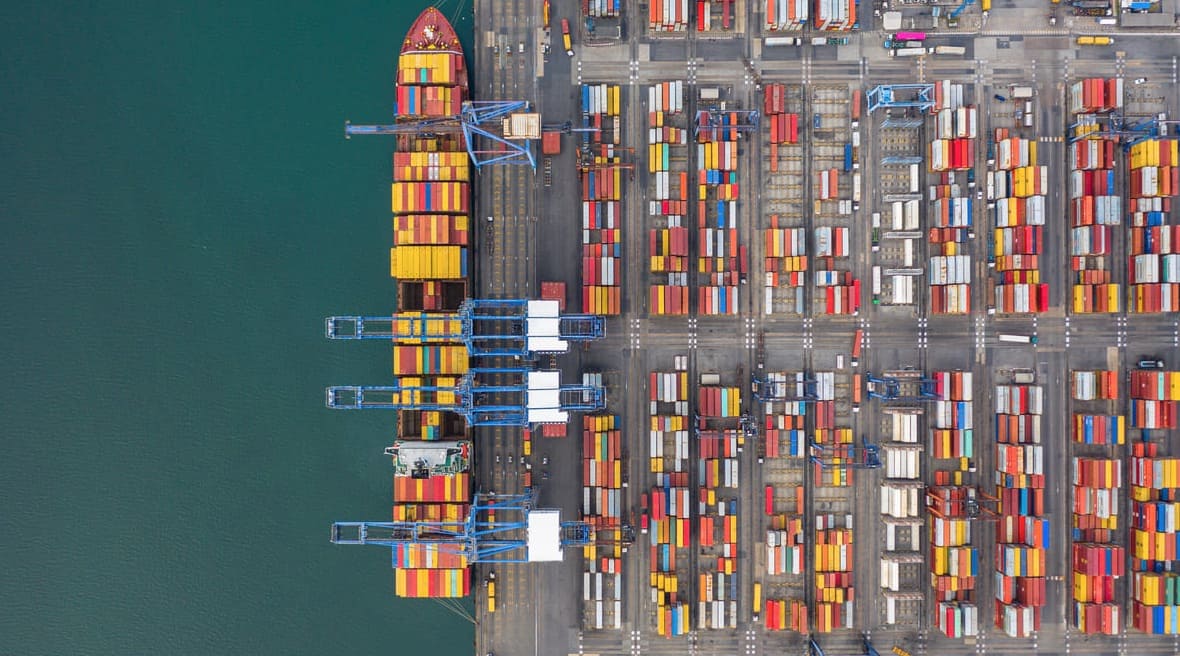

The global shipping emissions tax, spearheaded by the European Union and Pacific Island nations, aims to combat maritime pollution, which accounts for approximately 3% of global CO2 emissions. This initiative is modeled after the EU’s Emissions Trading System (ETS), which included maritime traffic in 2024.

The proposed flat tax would impose a fixed levy per ton of greenhouse gas emitted by ships. The revenue would incentivize the adoption of cleaner fuels and support ecological transitions, particularly in developing countries. Unlike the ETS, where carbon credit prices fluctuate, this tax would set a fixed rate based on the ship’s lifecycle.

Key benefits of this tax include promoting low-emission technologies such as ammonia, hydrogen, and biofuels. Experts estimate annual revenues could exceed $80 billion, providing substantial funding for green innovations.

Challenges and Opposition to the Global Shipping Emissions Tax

While gaining traction, the tax faces significant opposition from countries like China, Brazil, and Argentina. These nations argue the policy could increase export costs, disproportionately impact economies reliant on maritime trade, and harm key industries such as Argentine beef and Chilean cherries. Critics also highlight unresolved issues, such as the distribution of funds and their management.

Liberia and Panama Tip the Scale in Favor

Despite opposition, Liberia and Panama’s support shifts the momentum toward implementing the tax. According to the Financial Times, this coalition now controls a majority of the world’s shipping capacity.

However, even among supporters, disagreements remain. For instance, Liberia proposes a flat rate of $18.75 per ton of CO2, while nations like the Marshall Islands advocate for a significantly higher rate of $150 per ton. These differences will likely shape the policy’s final structure.